June German dance, Rocky Mount

|

GOING TO TOWN . . .

CHAPTER EXCERPTS

Tobacco Towns

he Coastal Plain, its broken topography still not knitted by compensatory highways and railroads, developed no sizable urban area even by North Carolina standards. Wilmington, with less than 50,000 inhabitants, was the largest place east of Raleigh but still somewhat isolated from the rest of the state. More representative of the very gradual urbanizing process in the east was a cluster of towns in the central Coastal Plain: Rocky Mount, Wilson, Greenville, Goldsboro, and Kinston. he Coastal Plain, its broken topography still not knitted by compensatory highways and railroads, developed no sizable urban area even by North Carolina standards. Wilmington, with less than 50,000 inhabitants, was the largest place east of Raleigh but still somewhat isolated from the rest of the state. More representative of the very gradual urbanizing process in the east was a cluster of towns in the central Coastal Plain: Rocky Mount, Wilson, Greenville, Goldsboro, and Kinston.

The five towns ranged in population from Kinston (22,000) to Rocky Mount (34,000), with only Greenville undergoing any significant increase in the 1960s. Kinston and Goldsboro actually declined during the decade. In 1860 all but Rocky Mount had been among the ten largest towns in the state; in 1970 none was. Such prosperity as they enjoyed could be attributed largely to the fact that they were the five largest bright leaf tobacco markets in the world, with Wilson the world leader.

The tobacco towns that fared best were those that had something extra going for them besides the leaf and some small industrial concerns. The ability of Goldsboro, for example, to maintain a faltering pace owed much to the federal government.

The slight, relative advantage at Wilson was mainly Atlantic Christian College (now named Barton College), Hackney Body Works, and 2 million square feet of tobacco warehouse space (including Smith's, the world's largest tobacco auction market).

Greenville faced much the same economic strains of fluctuating markets and black and white exodus as the other towns but weathered them better because of the expansion of its college. East Carolina Teachers College ("Eeseeteesee," as it was known down east), originally a girls' school, was long an ugly duckling in North Carolina's extensive system of higher education. A period of aggressive leadership after World War II carried it rapidly to higher status as East Carolina College and, ultimately, East Carolina University, complete with a medical school and big-time athletics.

Berry O'Kelly

|

East Hargett — Various factors, not always discriminatory, combined in the first decades of the twentieth century to concentrate black business along a stretch of Raleigh's East Hargett Street, which became, in effect, the city's "Negro Main Street." Prominent black commission merchant Berry O'Kelly acquired the real estate for the district. O'Kelly began as a small merchant in the community of Method, now part of Raleigh.

East Hargett Street early gained a good reputation in the city. Distinctly middle-class, it drew black doctors, lawyers, tailors, beauticians, dentists, and barbers, as well as black insurance companies and undertakers, a black theater, hotel, and bank, and a wide assortment of retail stores. But the street was at least as important socially as it was economically.

The 1940s brought changes in the character of East Hargett, but the street continued to be the focus of black business in the Raleigh area. Traffic and parking congestion drove some of the doctors, undertakers, and other professionals elsewhere in quest of more space. Many businesses previously owned by one individual became partnerships or corporations, while a general improvement in the civil position of blacks made them less dependent upon black-owned businesses. Gradually, East Hargett Street became more impersonal in its business style, less important in its social dimension. But the street in its heyday provided the black community with services and opportunities that were available through no other channel. In Asheville, a similar successful black business venture was the Young Men's Institute.

Colossalopolis — Demographers and urban planners looking toward the twenty-first century foresaw huge supercities stretching north and south from Los Angeles on the Pacific Coast and from Boston southward to the Potomac in the East. From the perspective of 1970, North Carolina seemed unlikely in the foreseeable future to become engulfed in any such urban sprawl, but the state's leading population centers were, indeed, beginning discernibly to merge. This raised the prospect of a vast, uninterrupted urban complex, a "Charleigh" or "Ralotte" that would pave the tobacco fields of the Piedmont and make parks of its rolling forests.

The term "Triangle" was already frequently heard for the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill area, though distinct rural expanses still largely separated the three. "Triad" would soon be coined to designate the Greensboro-Winston-Salem-High Point area, and a contest in the Charlotte vicinity in 1968 had brought forth the term "Metrolina" as the label for the urbanized region of which Charlotte was the hub. Moreover, all three of these incipient supercities formed points along a 300-mile strip reaching from Lynchburg, Virginia, to Anderson, South Carolina, that seemed likely to become a southern version of megalopolis by the year 2000. At the end of the twentieth century, North Carolina's population exceeded 8 million, and 5.4 million (68 percent) of the state's inhabitants were living in urban areas.

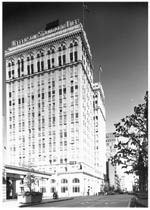

Jefferson Standard Building (1923), Greensboro

|

Metrolina embraced everything within a fifty-mile radius of Charlotte. It included Rock Hill, South Carolina and the North Carolina towns of Hickory, Salisbury, Shelby, Monroe, and others regarded as being in some degree related—by proximity to Charlotte or to one another. Planners deemed it useful to think in terms of such urban systems as a means of coordinating various services and activities. The time had come, they declared, when municipalities could no longer "work in a vacuum of narrow local interests."

As the twentieth century drew to a close, urban planners puzzled over the contradiction inherent in the evolution of Metrolina and similar supercities. Vast numbers of people identified the good life with easy access to the amenities of big-city living, but most also felt that the good life meant abundant space between oneself and one's neighbors. The effort to reconcile these ideals underlay the city's evolution into an urban region and the fostering of regional, as opposed to local, attitudes and allegiances. Hence, Metrolina was already the object of a regional coordinating committee, an environmental concern association, an air quality control program, a soil and water conservation effort, an area development association, and other regional planning groups. Would Charlotte, Winston-Salem, Raleigh, and Greensboro eventually be boroughs within a megalopolis? In some respects, by the end of the twentieth century, they had become exactly that.

|