Women working in a cannery near Rocky Mount in the 1930s.

|

THE ELECTRIC CORNUCOPIA . . .

CHAPTER EXCERPTS

The Big Three

lthough North Carolina in 1920 might with ample justice have been called an agricultural state, by far the larger part of its wealth at this time came from manufacturing. The leading industries, each thriving on cheap labor and the local availability of raw materials, were tobacco, cotton textiles, and furniture. In the preceding twenty years, North Carolina had advanced from twenty-seventh to fifteenth among all the states in the value of manufactured articles. During the 1920s, it would become the leading industrial state in the Southeast. In this rapid advance lay the source of both the pride and the heartbreak of the Old North State. lthough North Carolina in 1920 might with ample justice have been called an agricultural state, by far the larger part of its wealth at this time came from manufacturing. The leading industries, each thriving on cheap labor and the local availability of raw materials, were tobacco, cotton textiles, and furniture. In the preceding twenty years, North Carolina had advanced from twenty-seventh to fifteenth among all the states in the value of manufactured articles. During the 1920s, it would become the leading industrial state in the Southeast. In this rapid advance lay the source of both the pride and the heartbreak of the Old North State.

The three major industries were largely concentrated in an area roughly the shape of a reaping hook. The tip of this configuration lay in Raleigh, the blade curving west and then southwest along the route of the Southern Railway through Durham, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem to Charlotte. The handle stretched westward from Charlotte, paralleling the South Carolina border to Rutherford County. In this Piedmont region were concentrated most of the main population centers of North Carolina.

The dominant power source for the major manufacturers was the Southern (later Duke) Power Company, established in 1904 by tobacco magnate James B. ("Buck") Duke. Other producers of electric power (Carolina Power and Light in the east, Tallassee in the west) served the state, but Southern controlled the industrial Piedmont, supplying energy from its hydroelectric stations on the Catawba River.

J. Spencer Love

|

Rags and Riches — Textiles ranked first among the leading industries of North Carolina. There were 700 mills within a radius of 100 miles of Charlotte, and others scattered across the state.

By 1920 North Carolina boasted the world's largest mills for the manufacture of hosiery (Durham), towels (Kannapolis), denim (Greensboro), damask (Roanoke Rapids), and underwear (Winston-Salem). Eighty-five percent of the nation's combed yarn—used primarily in the more expensive types of women's wear—was made in Gaston County's 100 mills. But much of this productivity was a response to inflated wartime demands, and the decade of the 1920s brought a gradual decline in the per capita consumption of textiles. Intense competition among thousands of small firms scattered all across the state also had adverse effects on the industry, which, like farming, entered the Great Depression in poor condition to cope with it. For a time in the 1920s, tobacco replaced textiles as North Carolina's industrial leader.

But the textile industry had its entrepreneurial geniuses who not only coped but also prospered even in the darkest interwar years. Probably the outstanding textile manufacturer in North Carolina was J. Spencer Love of Burlington.

With a business acumen seasoned by a keen interest in experimental fabrics and new technology, Love became a pioneer in the production of rayon, which gave Burlington its first big boost. In 1934 Burlington was the country's largest weaver of rayon fabrics. By the time of his death in 1962, Love had built Burlington Industries into the colossus of textile manufacturing.

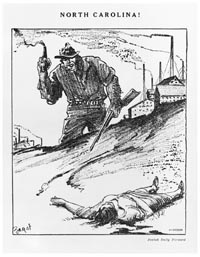

A textile strike at Loray Mill, in Gastonia, resulted in violence, including the shooting death of labor leader Ella May Wiggins, depicted in this drawing from Labor Age, October 1929.

|

Fruit of the Loom — Mounting distress among workers found expression in a new rash of textile strikes in early 1929 in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Most were spontaneous, with no unions involved, but three of the four in North Carolina were organized by the National Textile Workers' Union (NTWU), a Communist-led group. Far and away the most serious strike was that at the Loray Mill in Gastonia, reputedly the largest factory in the world under one roof.

Organized labor in North Carolina was dealt a setback of incalculable dimensions by the events of 1929 in Gastonia. The mutual antipathy of townspeople and workers there was not uncommon in industrial centers, and the memory of the strife is still a sore one in Gaston County.

Sporadic strikes have marked the history of North Carolina's textile industry since 1929. Wage cuts and poor working conditions brought cotton mill strikes at High Point, Rockingham, and elsewhere in 1932. Nearly a hundred North Carolina mills joined the general strike of 1934.

Affluence and Effluents — State government played an important role in the growth and dispersal of North Carolina industry, especially after Luther Hodges became governor in 1954. Hodges, a former textile manufacturer, rejuvenated the State Department of Conservation and Development and initiated the Building and Development Corporation to provide long-term capital for new and expanding industries. Hodges also sponsored tax concessions and an ambitious program of industry hunting, including missions to six nations of Western Europe. In the six years of his administration, the state gained over 1,000 new plants and the expansion of more than 1,400 others.

Hodges would be best remembered for his work in launching the Research Triangle. The basic idea had been bandied about for several years, chiefly through the interest of social scientist Howard W. Odum at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Romeo H. Guest, head of a Greensboro contracting firm. Hodges became interested in the possibility of using the research capabilities of the three major universities at Raleigh, Chapel Hill, and Durham as a lure to bring corporate laboratories and research centers to North Carolina. Through private contributions, the Research Triangle Institute acquired funds with which to purchase a tract of 4,000 acres of rural land lying within a "triangle" formed by the three schools. By 1959 the Research Triangle was a reality, its parks soon to be dotted with facilities representing Chemstrand, the U.S. Forest Service, IBM, Burroughs-Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and many more. Even more dramatically than the adjacent urban complexes, the Triangle Park sprouted glacial monoliths of steel and glass to soar above the embracing glades and pastures. Piedmont farming communities within the Triangle found themselves abruptly cheek-by-jowl with enclaves of Ph.D.'s and aerospace engineers. The twentieth century seemed almost to have been bypassed in a headlong plunge from the nineteenth century into the twenty-first.

Continuing tension between industry and labor was underscored by troubles at the Harriet-Henderson Cotton Mills at Henderson in the 1950s, the Roanoke Rapids plant of the J. P. Stevens textile firm, and elsewhere. Although the textile union eventually did organize J. P. Stevens employees, the success of the union movement in North Carolina was small compared to its success in the rest of the country. Only about 10 percent of the workers in the state are now union members. The national average is about 25 percent.

With industrial growth came industrial waste. The valuable commercial fishing industry began to feel the effects of chemical pollutants, which damaged the wetlands and rich shellfish grounds along the coast. Areas of scenic beauty and archeological significance were not always defended against the consequences of urban and industrial sprawl, nor the state's population protected from the daily hazards of air and water pollution, which brought on respiratory and other health problems.

|