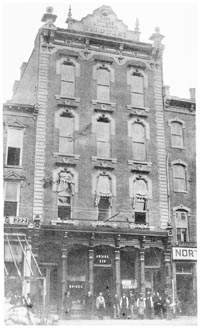

Briggs Hardware Store (1874), Raleigh

|

THE URBAN MAGNET . . .

CHAPTER EXCERPTS

o North Carolina city joined in the mushrooming of the nation's metropolises. There were only six towns with populations over 10,000 at the turn of the century, and the state's largest city in 1920 had just over 30,000 souls. Yet, during the fifty years after 1920, a steady evolution and cumulative change was evident. Towns and small cities became magnets for the ambitious and the restless, as well as havens of hope for those forced off the land by rural poverty. Decade by decade, more North Carolinians made town their home: one in twenty-five in 1870, one in ten in 1900, one in four by 1930. o North Carolina city joined in the mushrooming of the nation's metropolises. There were only six towns with populations over 10,000 at the turn of the century, and the state's largest city in 1920 had just over 30,000 souls. Yet, during the fifty years after 1920, a steady evolution and cumulative change was evident. Towns and small cities became magnets for the ambitious and the restless, as well as havens of hope for those forced off the land by rural poverty. Decade by decade, more North Carolinians made town their home: one in twenty-five in 1870, one in ten in 1900, one in four by 1930.

Of course, there were small towns in North Carolina before 1870, but not all were to expand after the Civil War. Absolutely essential for growth was a railroad line. Then a town might add tobacco factories, as did Durham and Winston, or become a center of the textile industry, as did Greensboro and Charlotte. With a railroad connection, Tarboro, in Edgecombe County, could expand as a marketing center for cotton and tobacco, and Hamlet, in Richmond County, could become a flourishing junction for passengers of the Seaboard Railroad Line.

Main Street — A vigorous middle class prospered in North Carolina's towns and created and supported a diverse array of stores and services. Carolinians who once had bartered for their goods at the antebellum gristmill or who had traded for necessities at the postwar country store, now had new options. At the Briggs Hardware Store in downtown Raleigh, for example, the customer found everything in the hardware line. A large sign and tantalizing wares at the entrance drew the shopper into T. H. Briggs's four-story red-brick store, which in 1874 was "the tallest building in East Carolina and Raleigh's first skyscraper." Buyers might gossip for a few minutes and warm themselves by the stove, but there was rarely the marathon of talking that characterized the country store. The order was placed, service was prompt, the purchase was made. Part of the pleasure in the high-ceilinged store, with its skylight letting in shafts of sunshine from above, was watching the clerk roll the wooden ladder to just the right place, climb high, and pluck down the merchandise in the quantity desired. Even though it was a store of staples, Briggs—like most enterprising merchants—always stocked the new and the novel and invited his customers to try "the latest." A Briggs advertisement in 1877 listed, among it wares, builders' supplies, house furnishing goods, stoves, ranges, sporting goods, guns, paints, oils, varnishes, and wagon and buggy materials.

Zollicoffer's Law Office (1887), Henderson

|

A. C. Zollicoffer moved from Halifax County to Henderson at the age of twenty-eight to open up a law practice and soon hung his shingle on the small Main Street office that has remained in the family for three generations. Much of his practice focused on the usual staple of the law—deeds and defaults, battery and bankruptcy—and he spent as many hours with red, leather-bound, oversized mortgage books as he did palavering in his office with clients. Zollicoffer's comfortable and habitable office, and his reputation as an attorney who could skillfully litigate a suit but who preferred to negotiate a settlement, won him loyal clients over the years. It was a measure of the lawyer's standing and the community's enterprise that he also represented the town's largest corporations: its textile mill, bagging company, and biggest bank.

Victorian Homes — The widening network of railroads, the dramatic expansion of industry, and the gradual growth of towns and cities brought a new measure of well-being to middle- and upper-class North Carolinians. Reflected in proud new civic and commercial buildings, that wealth also found expression in private residences and suburban development. Though quite different from each other, the Propst House of Hickory and "Körner's Folly" of Kernersville, the suburban homes of Dilworth in Charlotte and the R. J. Reynolds country estate in Winston-Salem, all illustrate shared principles of design that became common after 1880 in homes of the prosperous. Each offered a more spacious enclave for family privacy, and each presented a vivid architectural display of newfound wealth.

The Propst House in Hickory is the stuff of which nostalgia is made. There is a lightness, an airiness, a genteel whimsy about the late-Victorian dwelling. It is more than fantasy, more than a languid longing for a simpler age gone by that endows this home with its aura of charm. The house was designed by its owner, J. Summie Propst, a skilled builder and woodcarver, who erected it between 1881 and 1885.

Körner's Folly (1880), Kernersville

|

At first glance, the home of Jules Körner of Kernersville, about ten miles east of Winston-Salem, seems to deserve the name given to it by contemporaries: Körner's Folly. Built in 1880, the three-story, twenty-two-room residence spreads every which way. A multiplicity of heights and levels and a myriad of building materials give it the appearance of a miniature castle, misbegotten in stone, wood, and eight different sizes of handmade brick. Its sharply pitched roof swarms with spirelike chimneys; recessed arches and narrow windows endlessly ornament the facade.

The interior of Körner's singular dwelling is even more eclectic. There are seven levels in the house, connected by a maze of halls and winding stairways. No two doors are of the same dimensions.

Suburban Sanctuary — In 1891 an aggressive forty-one-year-old entrepreneur from Charlotte, Edward Dilworth Latta, announced that his newly formed Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company (the 4Cs) planned to develop a suburban community at the southern outskirts of the city on a rural site that had formerly been the city fairgrounds.

House (private residence) on East Boulevard Street, Dilworth neighborhood, Charlotte.

|

The southern suburb of Dilworth in the early twentieth century, then, was spacious and comfortable, affordable to the middle class, and as communal or private as its residents wished it to be. A financial bonanza for developers, it became a residential sanctuary for rising social classes, a world promoted and designed to screen out the hubbub of the city and to recreate—in idyllic parks and grassy lawns—the wholesomeness of the countryside.

In a similar fashion, other suburbs developed. In 1912, Myers Park, also a Charlotte suburb, was planned as another trolley-line community. Wide boulevards and tree-lined winding streets, with low-lying areas reserved as parkland, made it aesthetically pleasing. Telephone and electric wires were confined to rear lot lines, and commercial services were unobtrusively provided. Elizabeth (now Queens) College was its centerpiece. Trinity Park, in Durham, was a college-centered development too. Begun in the 1890s, it was laid out in a grid pattern with its utility lines run in back alleys between the streets. Formed from the estate of Brodie Duke, son of Washington Duke, it provided a housing area adjacent to Trinity College (now Duke University). The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw a decided improvement in the quality of city life. Frame Buildings gave way to brick or stone, sewerage and telephone systems were introduced, electric streetcars replaced horsecars, and electric lights replaced gaslights along the streets.

Reynolda House (1917), on the estate of tobacco baron R. J. Reynolds in Winston-Salem.

|

Manor with a Mission — In its heyday, the country estate of R. J. Reynolds and his wife, Katherine Smith Reynolds, had everything that whim could wish for and money could buy. Reynolda House, open to the public since 1964 as a showcase of American paintings and a learning center for the arts, was in 1917 the centerpiece of a domain of a thousand acres. Nestled in farmland a long, winding two miles from downtown Winston-Salem, the country place had polo fields, a nine-hole golf course, a pure-water swimming pool, a formal English garden, a cutting garden and greenhouse, a life-sized doll house for the two Reynolds girls, and a log cabin for the two boys. The main dwelling itself had sixty rooms, furnished with sumptuous elegance then and now. In the 1930s the family would add a bowling alley, game room, shooting gallery, enclosed swimming pool, and eight-room guest wing. For almost a half-century, Reynolda served its owners and their guests as an oasis of splendor and a recreational paradise.

Like other tobacco magnates and men of wealth who made their fortunes through the industrialization of the New South, R. J. Reynolds lived in town during the nineteenth century. His home was not far removed from his factory and from the employees who labored on his behalf.

A country estate that attempted to blend beauty, business enterprise, and educational uplift—it was a fascinating and ambitious vision. But then Katherine Smith Reynolds, like many of her generation, was a fascinating and ambitious woman. Katherine Smith was twenty-five years old in 1905 when she wed R. J. Reynolds. He was fifty-four.

Contemporaries of Katherine Smith Reynolds in North Carolina and elsewhere would not always find it possible to combine beauty and business, welfare and wealth. The concern of other women for the well-being of workers and the fate of farmers more than once led them on a collision course with the state's business leaders over issues of child labor, factory hours, and rural poverty. But, for the wife of R. J. Reynolds and the founder of the Reynolda farm, no such conflict emerged between what was progressive and what was profitable. The Reynolda estate—millionaire's rural retreat, model farm—married the best of both worlds.

|