Early settlers arriving in North Carolina. Courtesy of William S. Powell.

|

THE FOREST, THE INDIANS, AND

THE YEOMAN FAMILY . . .

CHAPTER EXCERPTS

hen they agreed on little else, travelers to North Carolina in the 1770s and 1780s concurred about the forest. Trees were everywhere: tangled oaks and cypresses where the ground was swampy in the east; stately pines where it was dry. To the west, oaks, hickories, walnuts, chestnuts, poplars, and an astonishing variety of other species took over, but always there were woods—dark, forbidding, and dense. By 1770 permanent European settlers had lived in this environment for over a hundred years, but still the wilderness felt very close. Whatever the people of North Carolina accomplished in the name of civilization—the houses they built, the fields they cleared and planted, the towns they made by the riverbanks—all took shape against a backdrop of seemingly endless forest. hen they agreed on little else, travelers to North Carolina in the 1770s and 1780s concurred about the forest. Trees were everywhere: tangled oaks and cypresses where the ground was swampy in the east; stately pines where it was dry. To the west, oaks, hickories, walnuts, chestnuts, poplars, and an astonishing variety of other species took over, but always there were woods—dark, forbidding, and dense. By 1770 permanent European settlers had lived in this environment for over a hundred years, but still the wilderness felt very close. Whatever the people of North Carolina accomplished in the name of civilization—the houses they built, the fields they cleared and planted, the towns they made by the riverbanks—all took shape against a backdrop of seemingly endless forest.

The famous Cherokee Sequoyah, depicted with his syllabary, which he devised to enable his people to become literate.

|

The Cherokee Indians were the last major tribe to control a section of North Carolina. They were not forced to surrender the final remnant of their mountain homeland until 1835, but white settlement of the Piedmont—or backcountry, as it was known—proceeded very rapidly in the 1750s and 1760s. Among the multitude of immigrants who found homes there, four groups were outstanding. Probably the largest number were Scotch-Irish, the descendants of Scottish Presbyterians who had colonized northern Ireland in the seventeenth century and moved from there to Pennsylvania and Maryland in the early eighteenth century. When population growth made these colonies seem crowded, second-generation families loaded their possessions into wagons and began to follow the Shenandoah Valley southward in search of cheap and fertile land. They filled up western Virginia first and then began to flood the North Carolina Piedmont at midcentury.

A harmonious relationship between human beings and nature was particularly important in the traditional culture of the American Indians. A combination of simple agriculture and hunting and gathering food from the forest environment enabled the Indians to maintain themselves comfortably without making heavy demands on the land or its resources. The Cherokees, for example, believed that disease was animals' retaliation for man's hunting them; each one contributed a specific ailment. But they also believed that plants took pity on man and each offered a cure to counteract a specific disease. Hence, the Indians depended heavily on herbal remedies.

The arrival of massive numbers of whites made the Indians' way of life increasingly precarious because the intensive land-use patterns of the Europeans were incompatible with the Indians' farming and hunting practices

A striking difference between white and Indian cultures lay in their respective attitudes toward wealth and material possessions. Before the arrival of whites, Cherokees traded with other tribes for needed materials, but they did not expect to gather a larger and larger surplus every year in order to trade for a profit. The tribe gathered food and meat for their yearly needs but no more than that. Indeed, personal property was buried with the dead and household possessions were destroyed annually in a major ceremony marking the beginning of the year. Because there was no incentive to use the labor of others to accumulate surplus property, slaves did not work much harder than their masters. A slave thus increased his master's prestige but not his wealth. In fact, Cherokee men kept few possessions of any kind besides clothing, weapons, and the trophies of battle because fields belonged to women and scratching in the dirt in search of useless riches was beneath the dignity of a warrior. Initially, the white man's love of acquisition invoked only the contempt of the Cherokees. On seeing the ostentatious Tryon Palace, Methodist minister Jeremiah Norman was reminded of the Indian saying: "White men build great & fine Houses as if they were to live allways, but white men must die as well as Red men."

Between 1777 and 1819 Cherokees ceded a total of 8,927 square miles to whites in North Carolina alone. When the tribe was finally reduced to a tiny fragment of its once-expansive domain, opponents of further cessions finally forced a halt, and the Cherokees sold no more land until they were forcibly ejected from the southern Appalachians in the winter of 1838-39.

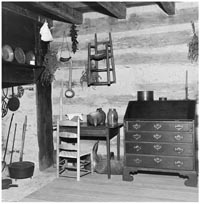

Main room in the Allen House.

|

One white missionary who lived among the North Carolina Cherokees in the years before removal reported that "their cabins are not much inferior to those of the whites of the neighborhood." Housing was not the only area of resemblance between Cherokee culture and the lifestyle of the pioneer white family. The large majority of these white settlers were called "yeomen." People of this class were small farmers and livestock producers who owned their own land and tilled it with their own labor. Like the Indians, white yeomen had limited contact with the market economy and depended for subsistence on the yield of the fields and the surrounding forests. A series of small houses in the Piedmont and central Coastal Plain reveals repeatedly the patterns of wilderness adjustment experienced by these men and women and their families. One of the simplest examples now stands on the Alamance Battleground State Historic Site, the home of John Allen (1749-1826) and Rachel Stout Allen (1760-1840). Built in 1782, the house stood for many years on the Allen family farm near Snow Camp before it was moved to its present site and restored in 1967.

|